"We are losing our attitude of wonder, of contemplation, of listening to creation and thus we no longer manage to interpret within it what Benedict XVI calls 'the rhythm of the love-story between God and man.'"

+ Pope Francis

A farewell tribute: The making of the once and future "green pope"

My writings on the Catholic perspective of ecology owe much to Pope Benedict XVI. This blog in particular has provided a real-time examination of the pontiff’s words and deeds related to abiding by and protecting nature.

And now—with the sudden and shocking news of his renouncing the Chair of Peter—we Catholic ecologists must say farewell to a pontiff that not only followed his predecessor’s ecological thought and practice, but escalated them well beyond what anyone had ever expected.

Indeed, Benedict XVI has been called the green pope by more than one news outlet. The question is, why this interest in ecology?

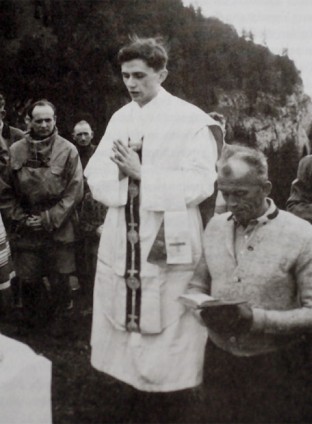

I have written many posts that examine that question. But here I think it’s helpful to examine that question by looking back on the development of Joseph Ratzinger’s theological and pastoral formation. In doing so, we find clues that make clear why this man spent so much of his pontificate speaking about a new reality for the human race: the destruction of our natural environment.

What follows is a look at a few key elements of his life and education that are important to his ecological pedigree.

First, as a young man, Ratzinger would watch nationalist zealotry—with its hunger for an imminent political glory—attempt to sweep aside his own Catholic Christianity along with other institutions, faiths, and peoples. In doing so, Hitler’s National Socialism would view itself in religious—indeed, eschatological—overtones. Ratzinger would witness the brutality of—and be forced to participate in—the armies of the Third Reich. National pride would swell when Hitler’s armies invaded Poland, The Netherlands, and France, when “even people who were opposed to National Socialism experienced a kind of patriotic satisfaction,” as the Holy Father noted in his biography Milestones. For others such as Ratzinger’s father, the march of the Third Reich were victories “of the Antichrist that would surely usher in apocalyptic times.”

In his humble biography, Ratzinger provides a small but telling example of the madness that his nation was undergoing: as a soldier he was forced to take part in a “cult of the spade,” a drill-like performance that he describes as a “pseudo-liturgy” meant to celebrate the redemptive power of a soldier’s work. Later, when Nazi military losses grew, the spades were used only for digging protective trenches: “[T]his fall of the spade from cultic object to banal tool for everyday use allowed us to perceive the deeper collapse taking place ... a full-scale liturgy and the world behind it were being unmasked as a lie.”

In contrast with this lie was Ratzinger’s growing relationship with a lasting truth. In recalling how as a boy he would be taught the mysteries of the Church’s liturgies, Ratzinger tells us something of how he sees the relation between the Church and history. He recalls that, as a boy learning of his faith,

it was becoming more and more clear to me that here I was encountering a reality that no official authority or great individual had created. This mysterious fabric of texts and actions had grown from the faith of the Church over the centuries. It bore the whole weight of history within itself, and yet, at the same time, it was much more than the product of human history. Every century had left its mark upon it ... [but] not everything was logical. Things sometimes got complicated, and it was not always easy to find one’s way. But precisely this is what made the whole edifice wonderful, like one’s own home.

Ratzinger’s post-war return home would occur in June 1945, when American forces released him from a prisoner-of-war camp. He made quickly for Traunstein, finding his family village at sunset filled with the hymns from its church—hymns sung in honor of the Feast of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

After the war, he returned to and advanced in his theological and priestly studies. In 1949 an adviser introduced him to a key influence in Ratzinger’s intellectual and personal development: Henri de Lubac and his book Catholicism; Christ and the Common Destiny of Man. Ratzinger notes that

this book was for me a key reading event. It gave me not only a new and deeper connection with the thought of the Fathers but also a new way of looking at theology and faith as such. Faith had here become an interior contemplation and, precisely by thinking with the Fathers, a present reality. In this book one could detect a quiet debate going on with liberalism and Marxism, the dramatic struggle of French Catholicism for a new penetration of the faith and into the freedom of an essentially social faith, conceived and lived as a we—a faith that, precisely as such and according to its nature, was also hope, affecting history as a whole, and not only the promise of a private blissfulness to individuals.

In Catholicism, Ratzinger would experience a thirst-quenching expression of the Eucharistic nature of the Church—a mystical body of real people living in authentic, gritty history. De Lubac’s forays into matters such as the “Role of Time” and “Doctrines of Evasion” (that is, evasions from the sufferings of this world) will illuminate Ratzinger’s observations of the secular forces that shaped the twentieth century.

In Catholicism, Ratzinger would experience a thirst-quenching expression of the Eucharistic nature of the Church—a mystical body of real people living in authentic, gritty history. De Lubac’s forays into matters such as the “Role of Time” and “Doctrines of Evasion” (that is, evasions from the sufferings of this world) will illuminate Ratzinger’s observations of the secular forces that shaped the twentieth century.

De Lubac would be a bridge connecting the twentieth century with the world of the Fathers—especially Augustine and Origen—and his eschatological worldview kept the faithful very much in, as Ratzinger put it above, the present reality and the weof the Church. De Lubac writes that “the Christian’s watchword can no longer be ‘escape’ but ‘collaboration’. He must cooperate with God and men in God’s work in the world and among humanity. There is but one end: and it is on condition that he aims at it together with all men that he will be allowed a share of the final triumph.”

Ratzinger will read such statements by de Lubac and watch Platonic circular concepts of history, per Augustine, “explode” so that “forthwith something new is wrought—birth, real growth; the whole universe grows to maturity. ... [T]he world has a purpose and consequently a meaning, that is to say, both direction and significance.” Ratzinger would turn also to de Lubac’s Corpus Mysticum, which, in Ratzinger’s words, would provide “a new understanding of the unity of the Church and Eucharist opened up to me beyond the insights I had already received ... [and so] I could now enter into the required dialogue with Augustine.”

This “dialogue with Augustine” is a third influence on Ratzinger’s views on theology and history. One can glimpse the importance of Augustine to Ratzinger in his autobiographical recollection of the appreciation with which he read Martin Buber’s philosophy of personalism. Ratzinger notes that Buber roused in him the same “essential mark” as had the Bishop of Hippo, “especially since I spontaneously associated such personalism with the thought of

Indeed, when a young Ratzinger read Augustine’s study of the collapse of

Indeed, when a young Ratzinger read Augustine’s study of the collapse of

Ratzinger appreciated Augustine’s correction to this refusal, The City of God—a text that would become a foundational work of Western civilization—in large part because it highlighted the humble entrance of the Word into world affairs. The City of

After his work on Augustine, he wrote a second doctoral thesis. This was required by the German theological academy for anyone seeking to teach. Ratzinger's topic for this thesis was St. Bonaventure's view of history and revelation. The thesis caused great turmoil in large part because of disagreement between Ratzinger's advisers. It may surprise some today to hear this, but some of these advisers challenged the young theologian that he would become "dangerously modern" with his work on Bonaventure's view of scripture having a "historical character." But Ratzinger (and the other advisers) won the day. The result was a substantial work that has added greatly to the Catholic academic corpus

Something else took place in writing this thesis that is important for the present conversation. Ratzinger's study of Bonaventure was specific to an episode within the young Franciscan Order. Not long after the death of Francis, a faction of the order known as the "spiritualists" found themselves at odds with orthodoxy. These Franciscans followed and somewhat misinterpreted the writings of a twelfth century abbot, Joachim of Fiore, who seemed to have made a series of intriguing predictions about a "new age" and who saw the story of the Church as an active one because history was far from stagnant—which, by the twelfth century, seemed fairly obvious.

The details of the matter are too great to delve into here. What is important for understanding Ratzinger's development and his eventual championing of Catholic ecology was how he witnessed in Bonaventure a pastor who was both unafraid of worldly change and was able to lovingly find ways to call errant members of his flock home. Bonaventure was able to offer the spiritualists a way back to orthodoxy by providing a fair reading of their works and finding aspects within it that had value. As a result, Bonaventure added to Christian thought the sense of revelation interacting with history—of grace baptizing new historical realities because of what Ratzinger would describe in his thesis as the "obligation" for disciples of Christ to sacrificially "love in the present."

From such influences, we can see how a young (and elderly) Ratzinger/Pope Benedict XVI stresses that Christian love—acting within history—is the antidote for all that disfigures the world.

All this is important to understand his ecological interests because science and current events are increasingly demonstrating the effects that man’s consumption is having on the natural world—and on human cultures.

For Ratzinger, man is at war with nature because we are too often at war with God. As

Until now.

Ecological issues began as rather local affairs but they are now global realities. Planetary systems of life are now compromised by man’s sin—our over-consumption, our ignoring of the laws of nature, and our refusal to seek first the

The young Joseph Ratzinger had an upbringing in his family and Church—in the stunning beauty of Bavaria—that allowed him a unique vision of the harm that man’s sin can cause and how, if we are to avoid this harm, we must accept God’s love and allow it to transform us in the actual moments of the present. For Pope Benedict XVI, a true culture of life is within our grasp only because God continually makes Himself present in the sacramental presence of the Church. The question, then, is if we accept this grace—this love—and allow it to change our inner selves, to reorient our human desires away from a consumption of worldly goods to an embracing of the God that is love.

For it is only by the grace of God that we humans will live in accord with—and thus protect—the nature of things.

Because of the presence of this man Joseph Ratzinger in the Church’s unbroken line of popes, his teachings will illuminate those of his successors until the end of time. Because Pope Benedict has made it clear that ecology is matter of magisterial importance, no future pope can now ignore the Catholic engagement of ecology. Indeed, it was ultimately the Holy Spirit that brought Joseph Ratzinger through his life and to the Chair of Peter and so has forever introduced to the Church’s teachings the place of ecology in Catholic thought and practice.

This last point is what the Holy Father has demonstrated in his departure from the role of pontiff. In his last homily on Ash Wednesday, Pope Benedict XVI said this

Our fitness will always be more effective the less we seek our own glory and the more we are aware that the reward of the righteous is God Himself, to be united to Him, here, on a journey of faith, and at the end of life, in the peace light of coming face to face with Him forever (cf. 1 Cor 13:12).

|

|

Photo: Flicker/ Catholic Church (England and Wales) |

These words are central to the Christian view of what it means to be human. They are also words that speak to how humans can live in accord with nature and keep it safe. But these are not simply the words of Pope Benedict. They are the promptings of the Holy Spirit and the teachings of Christ spoken in the present by the Vicar of Christ to a Church that is facing unprecedented global realities. Given Pope Benedict’s theological upbringing, he is able to speak of ecological issues and connect them with more basic realities of faith and reason. Thanks to his affinity for the likes of St. Augustine, St. Bonaventure, Henri de Lubac, and so many others, he knows that the Church is always able to dialogue with new realities because she possess the timeless truths of God.

We can be certain that the next Successor of Peter will continue on the path that Bl. John Paul II and Benedict XVI has taken the Church—a path that leads to an awareness of the ecological crises that now envelope the globe and a path that leads to the answer to these crises—to Christ, who alone can take away the sins of the world.

May God bless and protect our pontiff in his last days in service to us and may he be blessed and protected in his final days here on this side of